Tensor Processing Units(TPUs): The Silicon Engine Behind Modern AI Training

Every neural network training run burns through billions of matrix multiplications. Doing that on standard processors was never going to scale.

Now imagine if a chip was purpose-built for the exact math that powers deep learning. That idea, realized in Tensor Processing Units, changed how the world trains large models.

The Challenge Behind Training at Scale

Modern AI systems face a fundamental bottleneck: training a large language model like BERT or GPT requires processing trillions of floating-point operations. Multiply that by the need for faster experimentation cycles, and compute quickly becomes the limiting factor. Earlier approaches like CPU clusters or even GPU farms helped, but each involved trade-offs throwing more hardware at the problem at the cost of power consumption, cost, or programming complexity.

A simpler idea was treating neural networks as generic compute graphs. But what if we could design hardware specifically for the operations that dominate deep learning?

Understanding the TPU Advantage

Before we jump into how TPUs accelerate training, it helps to understand what makes them different from GPUs. In machine learning, the dominant operations are matrix multiplications massive batches of multiply accumulate operations that transform high imensional tensors.

GPUs were originally designed for graphics: rendering pixels, shading triangles, parallel texture mapping. They happen to be good at deep learning because graphics and neural networks both benefit from parallel computation. But GPUs are general purpose parallel processors.

NOTE: TPUs are not just "faster GPUs." They are application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) designed exclusively for the tensor operations that dominate neural network training—trading generality for raw efficiency in a specific domain.

This makes them incredibly efficient for model training, but it's a trade-off: TPUs excel at tensor math but are less flexible for arbitrary computations. While GPUs handle diverse workloads well, TPUs are purpose-built accelerators that shine when the workload matches their design.

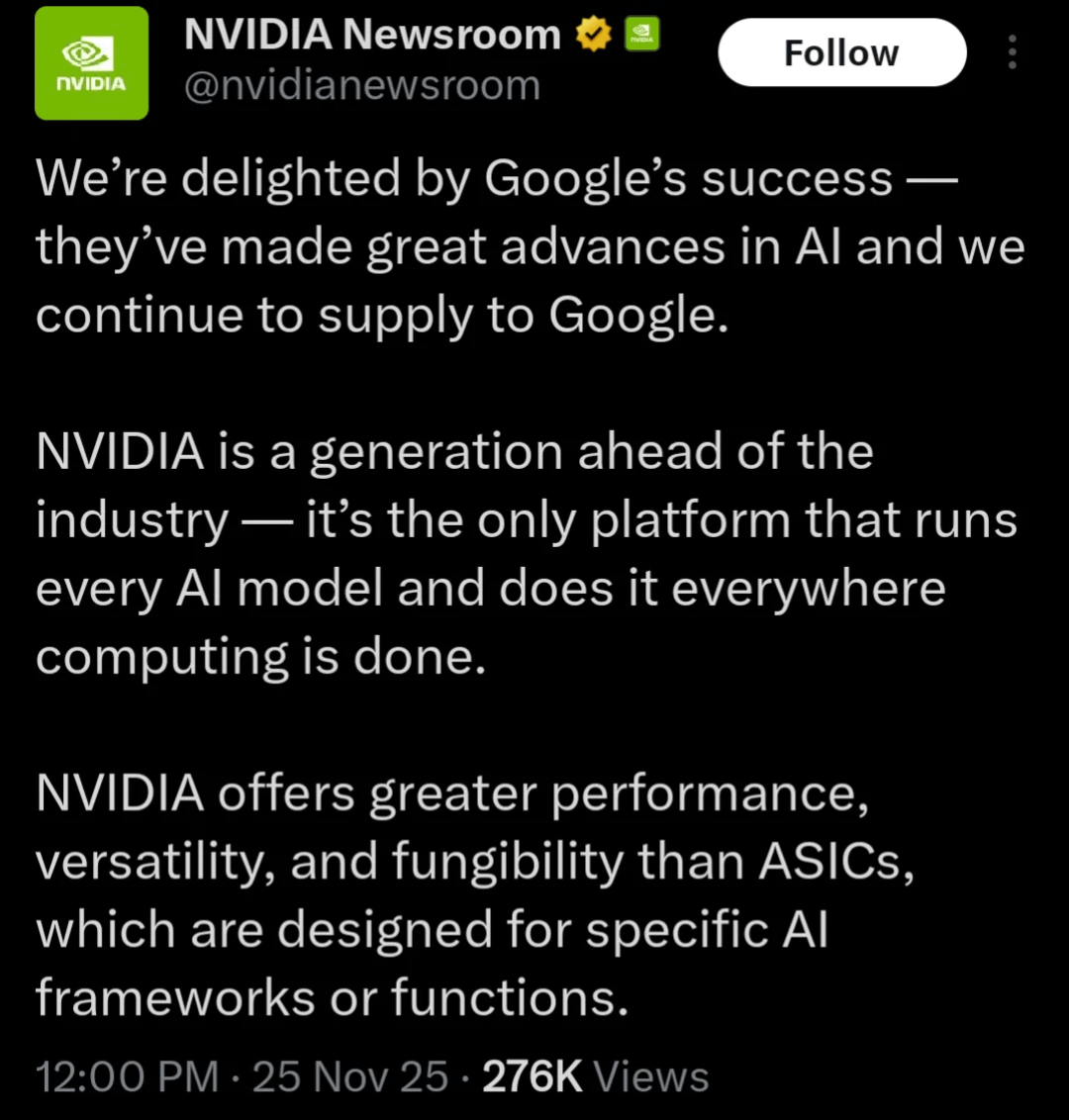

And yes, NVIDIA noticed. When Google announced major TPU deployments and deals, the GPU giant had... complicated feelings 😅:

Matrix Multiply Units(MXU)

Inside the TPU residesthe Matrix Multiply Unit (MXU), a massive systolic array that performs tens of thousands of operations per clock cycle.

TPU v4, for example, contains MXUs that can perform 275 trillion matrix multiply-accumulate operations per second. To understand why this matters, let's look at what actually happens in a neural network layer.

Given input matrix with shape (batch_size, hidden_dim) and weight matrix with shape (hidden_dim, output_dim), a dense layer computes:

output = input × weights + bias

The matrix multiplication alone requires batch_size × hidden_dim × output_dim multiply-accumulate operations. For a typical BERT-large layer with batch size 32, hidden dimension 1024, and intermediate size 4096:

Operations = 32 × 1024 × 4096 = 134 million MACs per layer forward pass

And that's just one layer. BERT-large has 24 of them. Plus backward passes. Plus multiple training steps.

if we look at how a simplified matrix multiplication looks in Python it looks like belwo,

# Input: batch of 32 sequences, each with 1024-dimensional embeddings

X = np.random.randn(32, 1024).astype(np.float32)

# Weights: projecting from 1024 to 4096 dimensions

W = np.random.randn(1024, 4096).astype(np.float32)

# Bias term

b = np.zeros(4096, dtype=np.float32)

# Standard matrix multiplication: 134M operations

Y = np.matmul(X, W) + b

print(f"Operations: {32 * 1024 * 4096:,} multiply-accumulates")

On a CPU, this executes sequentially. On a GPU, it runs in parallel across CUDA cores. On a TPU, the entire operation flows through a systolic array in a pipelined fashion—data moves rhythmically from one processing element to the next, like a factory assembly line for math.

Systolic Arrays

The breakthrough came from a simple insight: instead of fetching data repeatedly from memory, what if we arranged processing elements in a grid and passed data between them?

A systolic array is a 2D grid of processing elements where each element:

- Receives input from its neighbors

- Performs a multiply accumulate operation(MACs)

- Passes results to the next element

Figure: Systolic Array for Matrix Multiplication. Source: Wikipedia

Figure: Systolic Array for Matrix Multiplication. Source: Wikipedia

This pipelined approach means once the array is filled, it produces one result element per clock cycle with minimal memory access.

TPU Memory: High Bandwidth, On-Chip

Traditional architectures suffer from the von Neumann bottleneck: moving data between memory and compute units takes time and energy. TPUs address this with:

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) | Up to 32 GB with 1200 GB/s bandwidth per TPU v4 chip |

| On-chip SRAM | 144 MB of ultra-fast scratchpad memory |

| Communication links | Dedicated high-speed links for all-reduce operations |

The memory hierarchy is designed so that weights can be loaded once and reused across many operations, while activations flow through the MXU with minimal stalls.

Limitations of Traditional Accelerators

Traditional GPU training faces several constraints:

Core Limitations

-

Memory bandwidth bound When fetching data takes longer than computing, the processor sits idle waiting. GPUs often achieve only 30-50% of peak compute utilization.

-

Kernel launch overhead Each CUDA kernel launch has ~5-10 microseconds of overhead. With 100+ operations per layer, this adds up.

-

Limited on-chip memory GPU shared memory (~100KB per SM) requires frequent off-chip accesses for large models.

-

Communication bottlenecks All-reduce operations for gradient synchronization across GPUs become the bottleneck as cluster size grows.

-

Power efficiency General-purpose hardware wastes energy on features unused by ML workloads.

TPUs address these by co-designing hardware and software—XLA (Accelerated Linear Algebra) compiler fuses operations, minimizes memory transfers, and optimizes the entire compute graph for the MXU architecture.

XLA: The Compiler That Unlocks TPU Performance

The real magic happens in XLA (Accelerated Linear Algebra), Google's domain-specific compiler for linear algebra.

But what does XLA actually do? Think of it as a smart translator: it takes your high-level machine learning code (written in TensorFlow, PyTorch, or JAX) and converts it into optimized low-level instructions that run directly on TPU hardware. Instead of executing operations one by one, XLA analyzes your entire computation graph and figures out the most efficient way to run everything together.

XLA takes your TensorFlow/PyTorch/JAX code and:

- Fuses operations — Combines multiple ops into single kernels

- Eliminates intermediate allocations — Reduces memory traffic

- Optimizes layouts — Arranges tensors for efficient MXU access

- Automatic parallelism — Distributes computation across TPU cores

Here's what XLA compilation looks like in practice:

import tensorflow as tf

# Enable XLA compilation

tf.config.optimizer.set_jit(True)

# Or use the @tf.function decorator with jit_compile

@tf.function(jit_compile=True)

def dense_layer(x, w, b):

"""XLA will fuse matmul + add + activation into a single kernel"""

return tf.nn.gelu(tf.matmul(x, w) + b)

On TPU, this runs as one optimized operation instead of three separate kernels.

TPU Pods: Scaling Beyond Single Chips

A single TPU v4 chip is powerful. A TPU pod is transformative.

TPU v4 pods contain up to 4,096 chips interconnected with high-speed optical switches. This enables:

- Model parallelism — Splitting giant models across chips

- Data parallelism — Processing different batches on different chips

- Pipeline parallelism — Staggering computation across layers

The all-reduce bandwidth of 300 GB/s per chip means gradient synchronization happens fast enough that scaling efficiency stays above 90% even with thousands of chips.

Key Optimizations for TPU Training

Batch Size Matters

On TPU, batch size should be a multiple of 8 (for TPU v2/v3) or 4 (for TPU v4) times the number of TPU cores. This ensures even distribution across the MXUs.

Optimal Batch Size = k × num_cores × MXU_width

Use bfloat16

TPUs natively support bfloat16, a 16-bit floating point format that maintains the dynamic range of float32 while using half the memory:

# Enable mixed precision for automatic bfloat16 on TPU

tf.keras.mixed_precision.set_global_policy('mixed_bfloat16')

XLA is Essential

Always enable XLA compilation. Without it, you're leaving 3-5x performance on the table.

Quick Reference: TPU Generations

| Generation | Year | Peak Performance (BF16) | Memory | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPU v1 | 2016 | 92 TOPS | 8 GB HBM | Inference |

| TPU v2 | 2017 | 180 TFLOPS | 16 GB HBM | Training |

| TPU v3 | 2018 | 420 TFLOPS | 32 GB HBM | Large models |

| TPU v4 | 2021 | 275 TFLOPS/chip | 32 GB HBM | Massive scale |

| TPU v5e | 2023 | 197 TFLOPS | 16 GB HBM | Cost-efficient |

| TPU v5p | 2023 | 459 TFLOPS | 95 GB HBM | Largest models |

| TPU v6e (Trillium) | 2024 | 918 TFLOPS/chip | 32 GB HBM | Balanced performance |

| TPU v7x (Ironwood) | 2025 | 2,307 TFLOPS/chip | 192 GB HBM | Next-gen large-scale training |

References

-

Jouppi, N. P., et al. (2017). In-Datacenter Performance Analysis of a Tensor Processing Unit. ISCA 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1704.04760

-

Google Cloud. TPU Documentation. https://cloud.google.com/tpu/docs

-

TensorFlow. TPU Strategy Guide. https://www.tensorflow.org/guide/tpu

-

JAX Documentation. Using JAX on TPU. https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/jax-101/08-pjit.html